The Year of LiDAR

2022 is clearly the year of LiDAR. At all of the UAS shows in the USA, Mexico, Canada, and EU, the hot topic is LiDAR in 2022, and 2023 is ramping up to be more of the same, with significant growth. LiDAR is a “LIght Detection And Ranging” sensor, utilizing a laser, position-controlled mirror, an […]

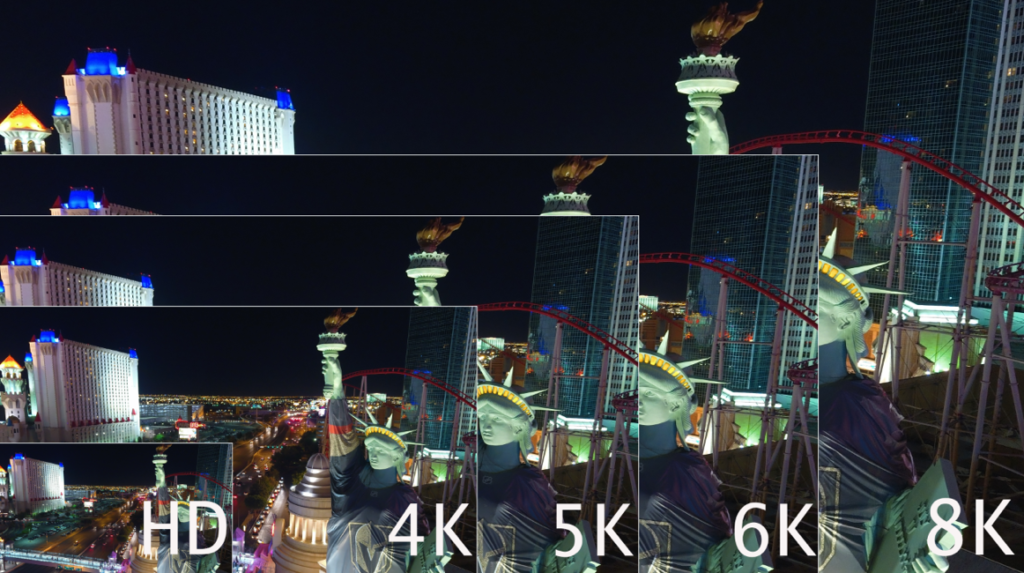

Does the Drone Industry Really Need 8K

We have to roughly quadruplemegapixels to doubleresolution, so the jump from SD to HD makes sense, while the jump from HD to UHD/4K makes even more sense. Following that theme, jumping to 6K makes sense, while jumping to 8K is perfect theory, and nears the maximum of the human eye’s ability to resolve information.

Experts Tested 4 Different Drone Mapping Solutions for Crime Scene Investigation

Experts Tested 4 Different Drone Mapping Solutions for Crime Scene Investigation. Here’s What Happened. At Commercial UAV Expo in Las Vegas, more than 300 drone industry professionals watched as experts tested four different drone mapping solutions for crime scene investigation at night. Guest post by Douglas Spotted Eagle, Chief Strategy Officer at KukerRanken Commercial UAV Expo brought […]

Selecting the Right Drone for Your Construction Business

Unmanned Aircraft (UA/Drones) have rapidly become a significant component of the modern construction industry workflow whether it’s for progress reporting, site planning, BIM, inventory control, safety awareness, structure inspection, topo’s, or other purposes. Site supervisors, architects, and stakeholders all benefit from the rapid output of accurate 2D/Ortho, or 3D models that may be used for purposes ranging from simple visualizations, progress reporting, stockpile calculations, DSM, contours, to more complex overlaying blue-prints in the As-Designed/As-Built or BIM process.