Selecting the Right Drone for Your Construction Business

Douglas Spotted Eagle and Brady Reisch headed into the field to collect aerial construction data over fourteen weeks with three different drones. Their goal was to determine which drone was best for the construction job site.

They used three popular aircraft for the comparisons and the results were pretty surprising.

Drones Compared:

- Autel EVO (½.3 sensor)

- Yuneec H520/E90 (1” sensor)

- DJI Phantom 4 (1”sensor)

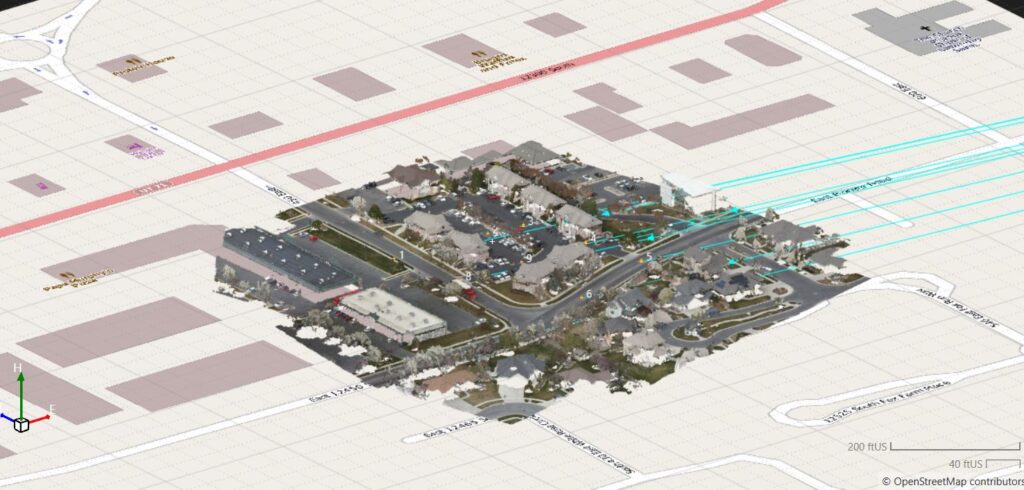

Unmanned Aircraft (UA/Drones) have rapidly become a significant component of the modern construction industry workflow whether it’s for progress reporting, site planning, BIM, inventory control, safety awareness, structure inspection, topo’s, or other purposes. Site supervisors, architects, and stakeholders all benefit from the rapid output of accurate 2D/Ortho, or 3D models that may be used for purposes ranging from simple visualizations, progress reporting, stockpile calculations, DSM, contours, to more complex overlaying blue-prints in the As-Designed/As-Built or BIM process.

Choosing the right aerial asset/UA may be challenging, particularly as the marketing of many UA is focused on RTK built in (rarely accurate) PPK solutions and a many component workflow versus others that are single-step workflows. Decisions on aircraft choices will be made based on budget, accuracy requirements, speed to result, and overall reporting requirements.

On any site flown for BIM, input to AutoDesk or similar tools, having accurate ground control points (GCP) is required. GCP’s may be obtained from the site surveyor, county plat, or other official sources, and this is often the best method assuming that the ground control points may be identified via UA flight-captured images. Site supervisors may also capture their own points using common survey tools. Devices such as the DTResearch 301 RTK tablet may be used to augment accuracy, combining GPC location points from the air and on the ground. Failing these methods, site supervisors can capture their own points based on the specific needs of the site. These points may be calculated via traditional rover/base RTK systems, or using PPK, RTK, or PPP solutions, again being budget and time dependent. If centimeter (vs decimeter) accuracy is required, RTK or PPK are necessary.

Putting accuracy aside, image quality is gaining importance as stakeholders have become accustomed to photo-grade ortho or models. Oftentimes, these models are used to share growth with inspectors as well, which means having presentation-grade images may be critical. Image quality is high priority when generating pre-development topos, or simply illustrating a tract of land from all directions. In other words, a high-quality imaging sensor (camera) is a necessity. Some aircraft allow user-choice cameras, while many UA manufacturers are creating cameras specific to their aircraft design.

Turning to aircraft, we chose three popular aircraft for the comparisons:

- Autel EVO (½.3 sensor)

- Yuneec H520/E90 (1” sensor)

- DJI Phantom 4 (1”sensor)

Flying the site several times in various conditions, the same RTK capture points are used in all three mapping projects. The DTResearch 301 RTK system is used to capture GCP on-location, with Hoodman GCP kit as the on-ground GCP. The Hoodman SkyRuler system was also captured as a scale-constraint checkpoint.

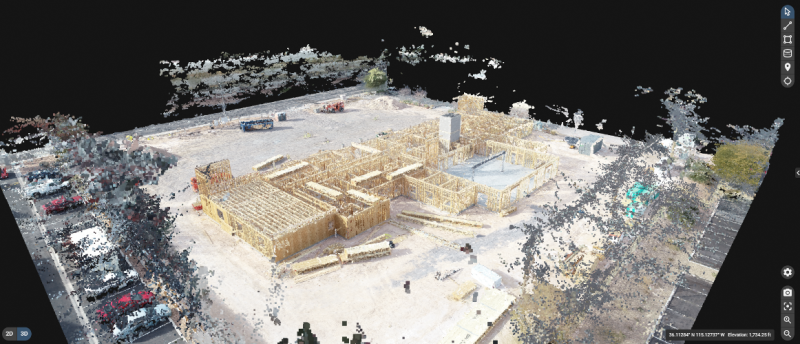

This commercial site is small in size (1.64 acres), and one we were able to begin capturing prior to forms being laid, all the way to vertical installation.

Accuracy varied greatly with each aircraft system, particularly in elevation calculations. Deviations are from projected points vs the GCP points obtained through a surveyor’s RTK system.

Overall (and to our surprise), the Autel EVO was most accurate with a deviation of:

- x-5.112ft

- y-47.827ft

- z-16.541ft

The Yuneec H520/E90 combo was not far behind with a deviation of:

- X-10.323ft

- y-44.225ft

- z-92.788ft

Finally, the DJI Phantom 4 presented deviations of:

- x-1.95ft

- y-45.565ft

- z-140.626ft

All of these deviations are calculated and compensated for in Pix4DMapper, which is used to assemble all of these week-to-week projects.

As 3D modelling was part of the comparison/goal, obliques were flown in addition to nadir captures. While manual settings are often essential for high quality maps and models, in the following images cameras were all set to automatic exposure, shutter, ISO.

It is important to remember that these are NOT corrected via network nor base station. This is autonomous flight, localized in Pix4D.

MODELS

All aircraft models work well with Pix4DMapper, although at the time of this writing, Pix4D has not created lens profiles for the Autel EVO (they have indicated this feature should be available “soon”). We custom-sized the lens profile ourselves, based on information provided by Autel’s product managers. *as of 2.1.22, Pix4D has generated lens profiles for both Autel EVO and EVO II aircraft.

Orthos

Although image quality is subjective, our client and our team all agree the Autel EVO provides the best image quality and color of all aircraft, with all aircraft set to automatic exposure, shutters peed, and ISO of 100. This is a surprise, given the Autel is a ½.3 imager, vs the 1” rolling shutter of Yuneec and global shutter of the DJI aircraft. Based on internet forums, Autel is very well known for their camera parameters being impressive.

All flights are single-battery flights. This is important, as changing batteries offers different functions for the various aircraft. Using Yuneec and DJI products and their respective software applications, we are able to fly larger sites with proper battery management with the aircraft returning to launch point when a battery is depleted and resume a mission where it left off once a fresh/charged battery is inserted. The Autel mission planner currently does not support multi-battery missions (although we’re told it will soon do so).

There are a few aspects to this workflow that are appreciated and some that are not. For example, when flying Autel and Yuneec products, we’re able to act as responsible pilots operating under our area wide Class B authorization provided by the FAA. To fly the DJI Phantom, the aircraft requires a DJI-provided unlock that permits flights. It’s a small annoyance, yet if one shows up on a jobsite not anticipating an unlock, it can be tedious. In some instances, we are just on the edge and outside controlled airspace, yet DJI’s extremely conservative system still requires an unlock. Most times, the unlock is very fast; other times, it doesn’t happen at all.

All three aircraft are reasonably fast to deploy, and this is important when a LAANC request for a zero-altitude grid is a short window. Autel clearly wins the prize for rapid deployment, with the EVO taking approximately 30 seconds to launch from case-open to in-the-air. Mission planning may be managed prior to flight and uploaded once the UA has left the ground. We are experiencing much the same with the latest release of the EVO II 1” camera as well. We also appreciated the lack of drift and angle in relatively high winds (26mph+).

DJI is next fastest at approximately three minutes, (assuming propellers remain attached in the case), while the mission planning aspect is a bit slower than the Autel system. DJI uploads the mission to the aircraft prior to launch. Of course, this is assuming we’ve already achieved an approval from DJI to fly in the restricted airspace, on top of the FAA blanket approval. If we don’t, we may find (and have found) ourselves unable to fly once on-site, due to glitches or slow response from DJI.

Yuneec is the slowest to deploy, given six props that must be detached for transport. Powering the ST16 Controller, attaching props, and waiting for GPS lock often requires up to five minutes. The mission planning tool (DataPilot) is significantly more robust than DJI’s GSPro, third party Litchi or other planning apps, and is far more robust than Autel Explorer’s mission planner. DataPilot also essentially ensures the mission will fly correctly, as it auto-sets the camera angle for different types of flight, reducing the margin for pilot error. The Yuneec H520 is superior in high winds, holding accurate position in reasonably high winds nearing 30mph.

All three aircraft turn out very usable models. All aircraft capture very usable, high-quality images. All of the aircraft are, within reason, accurate to ground points prior to being tied to GCP.

We were surprised to find we prefer the Autel EVO and are now completing this project after having acquired an Autel EVO II Pro with a 1” camera and 6K video.

Why?

Foremost, the Autel EVO family offered the most accurate positioning compared to the other aircraft in the many, many missions flown over this site. With dozens of comparison datasets, the Autel also offered the fastest deployment, and ability to fly well in high winds when necessary. The cost of the Autel EVO and EVO II Pro make this an exceptionally accessible tool and entirely reliable. That the Autel EVO requires no authorization from an overseas company, particularly in areas where we already have authorizations from the FAA, is significant to us, and the image quality is superior to either of the other aircraft.

We also greatly appreciate the small size of the aircraft, as it takes little space in our work truck, and our clients appreciate that we’re not invasive when working residential areas for them. The aircraft isn’t nearly as noisy as other aircraft, resulting in fewer people paying attention to the UA on the jobsite. The bright orange color, coupled with our FoxFury D3060 light kit (used even in daylight) assists in being able to see the aircraft quite easily, even when up against a white sky or dark building background.

We also of course, appreciate the speed in deployment. With safety checks, LAANC authorizations, planning a mission, and powering on remote and aircraft, the Autel EVO is deployable in under two minutes. When flying in G airspace, from case to airborne can be accomplished in under 30 seconds.

Battery life on the EVO 1 is substantial at 25 minutes, while our newly acquired EVO II Pro offers 40 minutes of flight time with incredible images to feed into Pix4D or other post-flight analytics software.

Of greatest importance, the EVO provides the most accurate XYZ location in-flight compared to the other aircraft. For those not using GPS systems such as the DTResearch 301 that we’re using on this project, accuracy is critical, and being able to ensure clean capture with accurate metadata is the key to successful mapping for input to Autocad applications.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE:

www.autel.com (UA, mission planning)

www.dtresearch.com (RTK Tablet with hyper-accurate antenna system)

www.dji.com (UA, mission planning)

www.foxfury.com (Lighting system for visualization)

www.hoodman.com (GCP, LaunchPad, SkyRuler)

www.Pix4D.com (Post-flight mapping/modelling software)

www.sundancemediagroup.com (training for mapping, Pix4D, public safety forensic capture)

www.yuneec.com/commercial (UA, mission planning)

With thanks to Autel, Hoodman, DTResearch, and Pix4D.